At my Ecclesiastical Council held back in January, I was asked about my theology of the Lord’s Supper. When I pressed the person asking the question to probe exactly what they were looking for in answer the questioner wanted to know what I thought happened during the Lord’s Supper. My answer was something along the lines of it does not matter what happens on the table it matters what happens after the table. In other words, I am not concerned about if a change takes place here, among the bread and the juice we have laid out for the celebration today, I am concerned about the change that takes place in you and me. The miracle, if you will, is not in some magic words prayed over bread and wine, the magic, the transformative powers of the Holy Spirit is the miracle when it changes us.

So I have placed the titles of “Do This…” on this sermon today, the World Communion Sunday, so we can focus on what it was that Jesus was asking us to do. Sure, I believe he was asking us to repeat what he was doing in that upper room on his last night with his Apostles, but I also think he was asking us to “Do” more.

This passage we heard this morning is the first time these words were written. Paul’s letters are some of the earliest written of the Christian Scriptures; they predate the Gospels by many years. The other interesting part of this is that Paul was not there and it is the first time the words of Jesus were written.

In these words, Jesus speaks about a covenant, a new covenant, a covenant in his blood.

Jesus is saying something like: “This cup is the new covenant, and it cost my blood.”

A covenant relationship is one entered into by two people, perhaps more, but at least two. The old relationship between God and the people was based on the law; there was a condition that the law had to be kept. With Jesus, the new covenant is based on love and not dependent on keeping the law; it is based on the free grace of God’s love offered to all.

But this new covenant goes much deeper than that because there is the “Do This…” associated with it. So what then is this “Do this?”

As followers of Jesus we believe that we are to imitate his life as best we can in our daily lives. We believe that the bible has been given to us not as a science or history book, but as a guide if you will for how we should live. My personal belief is that this is not to be taken literally but left to us as an example of what we should be able to do.

Jesus comes as the fulfillment of the law, no longer are we bound to obey to the letter of the law now we have the Spirit of the Law that guides us. We are to do what Jesus did, and that is our imitation.

Jesus cared for the least of these and spoke about it often. He does not seek out power, in fact, the only time he is “hangs out” with the powerful is when he is standing before Pilate just before his crucifixion. He was born humbly in a backwater town in the Roman Empire and had to flee to another country, without a visa by the way, for his life to be saved. It was to the marginalized that he ministered and to the powerful.

Jesus was found with the less desirable of the population, prostitutes, tax collectors, beggars, lepers, women, Samaritans and all the rest. He was reaching out to and ministering to the people that had no place in the temple, they had no seat at the table, and no one was listening to them. He healed the sick, pardoned those that humanity had cast out and in the end, it cost him his life. Make no mistake about it, Jesus was killed by the powerful because he threatened their way of life. Sure, he went willingly to the Cross, but it was those in power that pulled the trigger so to speak.

The Letter of St. James is one of my favorite books of the bible. It is called a Pastoral Epistle or Universal Epistle because it is written not to a particular church, as Paul has written, but to the entire church. James has a lot to say about “Doing This…”

“What does it profit, my brethren, if someone says he has faith but does not have works? Can faith save him? If a brother or sister is naked and destitute of daily food, and one of you says to them, “Depart in peace, be warmed and filled,” but you do not give them the things which are needed for the body, what does it profit? Thus also faith by itself, if it does not have works, is dead. But someone will say, “You have faith, and I have worked.” Show me your faith without your works, and I will show you my faith by my works.” (James 2:14-26)

He ends this section with these words:

“For as the body without the spirit is dead, so faith without works is dead also.”

But the words of Jesus sum it up best in the Gospel of Matthew:

“Then the righteous will answer him, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you something to drink? When did we see you a stranger and invite you in, or needing clothes and clothe you? When did we see you sick or in prison and go to visit you?’ “The King will reply, ‘Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.'” (Matthew 25:37-40)

Who are we to minister too? The least of these. Who are we care for? The least of these. Who are we to consider our neighbors? The least of these.

Francis of Assisi is often quoted as saying, “Preach the gospel every day, sometimes use words.” A person’s faith is not contained in a book, a person’s faith is held in dogma, a person’s faith is not even contained in bread and wine. A person’s faith is contained in how they treat the least of these.

Do have concern for the least of these. Do have concern for the poor and needy. Do have concern for the stranger among us. Do have concern for those who look different than us. Do have concern for the widows and orphans. Do have concern for those affected by storms, physical, mental, and natural. Do have concern for those affected by war. Do have concern for those yearning to have the same rights that you and I have. Do be concerned that we are not holding people to the letter of the law when we should be showing the spirit of the law. Do be concerned with and love your neighbor;

Your homeless neighbor

Your Muslim neighbor

Your black neighbor

Your gay neighbor

Your white neighbor

Your Jewish neighbor

Your Christian neighbor

Your Atheist neighbor

Your racist neighbor

Your addicted neighbor

Why? Because Jesus said, “Do This” in remembrance of me!

The leaders of the

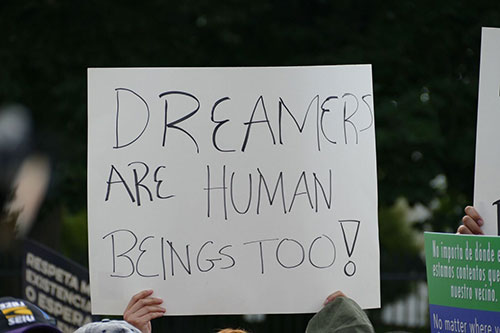

The leaders of the  A diverse group of faith, labor and student leaders took to the streets outside the White House today calling on Congress to pass legislation to protect the Dreamers, as Attorney General Jeff Sessions rescinded the DACA program. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) said there will be a six-month delay in enforcement and those with current work permits will be able to continue their employment until they expire, with renewals accepted until Oct. 5. But DHS will no longer take applications and will stop processing any new applications as of today.

A diverse group of faith, labor and student leaders took to the streets outside the White House today calling on Congress to pass legislation to protect the Dreamers, as Attorney General Jeff Sessions rescinded the DACA program. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) said there will be a six-month delay in enforcement and those with current work permits will be able to continue their employment until they expire, with renewals accepted until Oct. 5. But DHS will no longer take applications and will stop processing any new applications as of today.