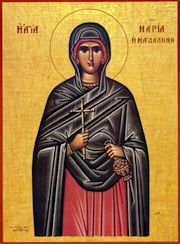

Tonight the Church invites us to focus our attention on two figures: the sinful woman who anointed the head of Jesus shortly before the passion (Mt 26.6-13), and Judas, the disciple who betrayed the Lord. The former acknowledged Jesus as Lord, while the latter severed himself from the Master. The one was set free, while the other became a slave. The one inherited the kingdom, while the other fell into perdition. These two people bring before us concerns and issues related to freedom, sin, hell and repentance. The full meaning of these things can be understood only within the context and from the perspective of the existential truth of our human existence.Freedom belongs to the nature and character of a human being because he has been created in the image of God. Man and his true life is defined by his uncreated Archtype, who, according to the Greek Fathers, is Christ. Man’s ultimate grandeur, in the words of one theologian, “is not found in his being the highest biological existence, a rational or political animal, but in his being a deified animal, in the fact that he constitutes a created existence which has received the command to become a god.” In the final analysis, man becomes authentically free in God; in his ability to discover, accept, pursue, enjoy and deepen the filial relationship which God confers upon him. Freedom is not something extraneous and accidental, but intrinsic to genuine human life. It is not a contrivance of human ingenuity and cleverness, but a divine gift. Man is free, because his being has been sealed with the image of God. He has been endowed with and possesses divine qualities. He reflects in himself God, who, someone has said, reveals Himself as personal existence, as distinctiveness and freedom.” The ultimate truth of man is found in his vocation to become a conscious personal existence; a god by grace. The elemental exercise of freedom lies in one’s conscious decision and desire to fulfill his vocation to become a person or to deny it; to become a being of communion or an entity unto death; to become a saint or a devil.Since man is able to resist God and turn away from Him, he can diminish and disfigure God’s image in him to the extreme limits. He is able to misuse, abuse, distort, pervert and debase the natural powers and qualities with which he has been endowed. He is capable of sin. Sin turns him into a fraud and an impostor. It limits his life to the level of biological existence, robbing it of divine splendor and capacity. Lacking faith and moral judgement, man is capable of turning freedom into license, rebellion, intimidation and enslavement.Sin is more than breaking rules and transgressing commandments. It is the willful rejection of a personal relationship with the living God. It is separation and alienation; a way of death, “an existence which does not come to fruition,” to use the words of St. Maximos the Confessor. Sin is the denial of God and the forfeiting of heaven. It is the seduction, abduction and captivity of the soul through provocations of the devil, through pride and mindless pleasures. Sin is the light become darkness, the harbinger of hell, the eternal fire and outer darkness. “Hell,” according to one theologian, “is man’s free choice; it is when he imprisons himself in an agonizing lack of life, and deliberately refuses communion with the loving goodness of God, the true life.”

To sin is to miss the mark, to fail to realize one’s vocation and destiny. Sin brings -disorder and fragmentation. It diminishes life and causes the most pure and most noble parts of our nature to end up as passions, i.e., faculties and impulses that have become distorted, spoiled, violated and finally alien to the true self.

Sin is not just a disposition. It is a deliberate choice and an act. Likewise, repentance is not merely a change in attitude, but a choice to follow God. This choice involves a radical, existential change which is beyond our own capacity to accomplish. It is a gift bestowed by Christ, who takes us unto Himself through His Church, in order to forgive, heal and restore us to wholeness. The gift He gives us is a new and clean heart.

Having experienced this kind of reintegration, as well as the power of spiritual freedom that issues from it, we come to realize that a truly virtuous life is more than the occasional display of conventional morality. The outward impression of virtue is nothing more than conceit. True virtue is the struggle for truth and the deliberate choice of our own free will to become an imitator of Christ. Then, in the words of St. Maximos, “God who yearns for the salvation of all men and hungers after their deification, withers their self-conceit like the unfruitful fig tree. He does this so that they may prefer to be righteous in reality rather than appearance, discarding the cloak of hypocritical moral display and genuinely pursuing a virtuous life in the way that the divine Logos wishes them to. They will then live with reverence, revealing the state of their soul to God rather than displaying the external appearance of a moral life to their fellow-men.”

The process of healing and restoring our damaged, broken, wounded and fallen nature is on-going. God is merciful and longsuffering towards His creation. He accepts repentant sinners tenderly and rejoices in their conversion. This process of conversion includes the purification and illumination of our mind and heart, so that our passions may be continually educated rather than eradicated, transfigured and not suppressed, used positively and not negatively.

The act of repentance is not some kind of cheerless, morbid exercise. It is a joy-bringing event and enterprise, which frees the conscience from the burdens and anxieties of sin and makes the soul rejoice in the truth and love of God. Repentance begins with the recognition and renunciation of one’s evil ways. From this interior sorrow it proceeds to the verbal acknowledgement of the concrete sins before God and the witness of the Church. By “becoming conscious both of his own sinfulness and of the forgiveness extended to him by God,” the repentant sinner turns freely towards God in an attitude of love and trust. Then he focuses his truest and deepest self, his heart, continually on Christ, in order to become like Him. Experiencing the embracing love of God as freedom and transfiguration (2 Cor 3.17-18), he authenticates his own personal existence and shows heartfelt concern, compassion and love for others.

I have transgressed more than the harlot, O loving Lord, yet never have I offered You my flowing tears. But in silence I fall down before You and with love I kiss Your most pure feet, beseeching You as Master to grant me remission of sins; and I cry to You, O Savior: Deliver me from the filth of my works.

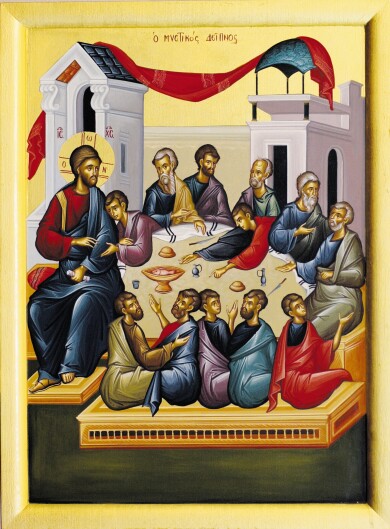

While the sinful woman brought oil of myrrh, the disciple came to an agreement with the transgressors. She rejoiced to pour out what was very precious, he made haste to sell the One who is above all price. She acknowledged Christ as Lord, he severed himself from the Master. She was set free, but Judas became the slave of the enemy. Grievous was his lack of love. Great was her repentance. Grant such repentance also unto me, O Savior who has suffered for our sake, and save us.

On Saturday, the high priests and Pharisees gathered together before Pilate and asked him to have Jesus’ tomb sealed until the third day; because, as those enemies of God said, “We suspect that His disciples will come and steal His buried body by night, and then proclaim to the people that His resurrection is true, as that deceiver Himself foretold while He was yet alive; and then the last deception shall be worse than the first.” After they had said these things to Pilate and received his permission, they went and sealed the tomb, and assigned a watch for security, that is, guards from among the soldiers under the supervision of the high priests (Matt. 27:62-66). While commemorating the entombment of the holy Body of our Lord today, we also celebrate His dread descent with His soul, whereby He destroyed the gates and bars of Hades, and made His light to shine where only darkness had reigned (Job 3 8 : 17; Esaias 49:9; 1 Peter 3:18-20); death was put to death, Hades was stripped of all its captives, our first parents and all the righteous who died from the beginning of time ran to Him Whom they had awaited, and the holy angelic orders glorified God for the restoration of our fallen race.

On Saturday, the high priests and Pharisees gathered together before Pilate and asked him to have Jesus’ tomb sealed until the third day; because, as those enemies of God said, “We suspect that His disciples will come and steal His buried body by night, and then proclaim to the people that His resurrection is true, as that deceiver Himself foretold while He was yet alive; and then the last deception shall be worse than the first.” After they had said these things to Pilate and received his permission, they went and sealed the tomb, and assigned a watch for security, that is, guards from among the soldiers under the supervision of the high priests (Matt. 27:62-66). While commemorating the entombment of the holy Body of our Lord today, we also celebrate His dread descent with His soul, whereby He destroyed the gates and bars of Hades, and made His light to shine where only darkness had reigned (Job 3 8 : 17; Esaias 49:9; 1 Peter 3:18-20); death was put to death, Hades was stripped of all its captives, our first parents and all the righteous who died from the beginning of time ran to Him Whom they had awaited, and the holy angelic orders glorified God for the restoration of our fallen race. On Saturday, the high priests and Pharisees gathered together before Pilate and asked him to have Jesus’ tomb sealed until the third day; because, as those enemies of God said, “We suspect that His disciples will come and steal His buried body by night, and then proclaim to the people that His resurrection is true, as that deceiver Himself foretold while He was yet alive; and then the last deception shall be worse than the first.” After they had said these things to Pilate and received his permission, they went and sealed the tomb, and assigned a watch for security, that is, guards from among the soldiers under the supervision of the high priests (Matt. 27:62-66). While commemorating the entombment of the holy Body of our Lord today, we also celebrate His dread descent with His soul, whereby He destroyed the gates and bars of Hades, and made His light to shine where only darkness had reigned (Job 3 8 : 17; Esaias 49:9; 1 Peter 3:18-20); death was put to death, Hades was stripped of all its captives, our first parents and all the righteous who died from the beginning of time ran to Him Whom they had awaited, and the holy angelic orders glorified God for the restoration of our fallen race.

On Saturday, the high priests and Pharisees gathered together before Pilate and asked him to have Jesus’ tomb sealed until the third day; because, as those enemies of God said, “We suspect that His disciples will come and steal His buried body by night, and then proclaim to the people that His resurrection is true, as that deceiver Himself foretold while He was yet alive; and then the last deception shall be worse than the first.” After they had said these things to Pilate and received his permission, they went and sealed the tomb, and assigned a watch for security, that is, guards from among the soldiers under the supervision of the high priests (Matt. 27:62-66). While commemorating the entombment of the holy Body of our Lord today, we also celebrate His dread descent with His soul, whereby He destroyed the gates and bars of Hades, and made His light to shine where only darkness had reigned (Job 3 8 : 17; Esaias 49:9; 1 Peter 3:18-20); death was put to death, Hades was stripped of all its captives, our first parents and all the righteous who died from the beginning of time ran to Him Whom they had awaited, and the holy angelic orders glorified God for the restoration of our fallen race.